to American Countryman: Essays On The Life Of Hal Borland. Look for additional posts in the months ahead. Though I do not intend to follow any chronological order, these essays (based on years of research) are collectively going to tell the story of Borland’s life and career. Hope you find them interesting. Follow or subscribe (it’s free) to receive email updates on future posts. Email addresses are kept confidential and not given to anyone. Leave comments or send feedback–let me know who you are and what you think, and thanks for stopping by.

When the Legends Die: Hal Borland’s American Classic

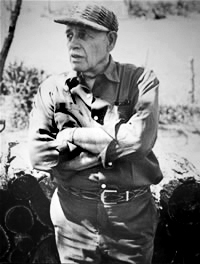

In March of 1966 Hal Borland wrote: “I didn’t plan to be a nature writer, but it has paid for the bread and dungarees when nothing else did. . .The fiction is, to me at least, wholly unpredictable. It’s an indulgence, with all the God-awful trash monopolizing the market.” Ironically, over a prolific career that spanned six decades and 36 published books, Borland would be hailed “the dean of American outdoor writers” by Publishers Weekly, and achieve his greatest success with a novel he called “nothing but a flyer on my part. I had no hopes for it.”

Harold Glen Borland was born in Sterling, Nebraska on May 14, 1900. Sterling, located on the Nemaha River in south-eastern Nebraska, had been settled only thirty years earlier, a product of the first great wave of homesteaders after the Civil War. Harold’s Grandfather was one of the town’s earliest citizens, having taken a homestead there in 1872. When Sterling incorporated in July 1876, Grandpa Borland, a blacksmith and expert wagon maker, had become a respected businessman and community leader, and was among Sterling’s first elected Board of Trustees.

Harold’s father, Will, was born in Sterling in 1878, one of sixteen children. In his early teens, Will apprenticed to The Sterling Sun newspaper, quickly reaching the level of master printer. At seventeen, Will left home to travel through eastern Nebraska and western Iowa, working for several papers and perfecting his skills. In these small country shops Will learned advanced techniques from “tramp printers,” highly skilled itinerant men who rode the freights from town to town, picking up work where they could find it. In 1896 he returned to Sterling to be with his dying father, and was at his bedside when he passed away in August. Will remained in Sterling, working as a freelance printer before taking a position as a sales advisor for a printing supply company based in Omaha. On April 26, 1899, he married eighteen-year-old Sarah Clinaberg from nearby Tecumseh, and, in 1907, became part owner and editor of The Sterling Sun, alongside the man who had first taught him the printer’s trade.

As a young boy in Sterling, Harold had what he years later described as “a kind of front row seat to. . .a way of life and a kind of living that was usual if not wholly typical of that time. The time, of course, was the beginning of the century and it just happened that the frontier was still a warm or at least a vivid memory.” He knew old trappers and farmers, Civil War veterans who had fought on both sides, had an uncle who was in the Spanish-American War. On visits to the Clinaberg’s farm in Tecumseh, Harold was thrilled to be included in berry picking excursions, learned canning and cooking skills, and helped cure beef and pork for the winter. He was especially fond of Grandma Clinaberg, an independent “pioneer matriarch” who would often tell her seven children that “every tub stands on its own bottom” and “the Lord helps those who help themselves.” Grandma Clinaberg knew when prime harvest time came in every season, and taught her children how to live with the land and make the best of all it offered.

Another local character who had a lifelong influence on Harold was “Old Phil,” an eccentric loner with wild long hair who lived in a shanty and trapped skunks and muskrats. Phil’s parents were killed when he was an infant. He was raised by Indians, trained as a scout, and served under General Custer until he was severely wounded and hospitalized only a week before the battle at Little Big Horn. Phil told exciting stories of Indian wars, grizzly bears, and massive buffalo herds that roamed the Plains not so many years earlier. To the children of Sterling Phil was a hero, “one of the last of the old scouts and frontiersmen.” From Phil, Harold learned basic survival skills and a lasting respect for nature.

In the first two decades of the twentieth century nearly a million homesteaders migrated west and settled on the Great Plains. In February 1910 a restless Will abruptly left his lucrative position at The Sterling Sun and filed a claim on the remote, short grass plains of eastern Colorado. The closest town was Brush, a full day’s wagon ride 30 miles north. The arid plains of eastern Colorado had long been considered suitable only for grazing, and, other than a few unwelcoming cattle and sheep ranchers, were largely uninhabited when Will took his claim in 1910. Harold and his father built a 14 by 20 foot shell for their home, then covered the roof and outside walls with “bricks” cut from the tough, ancient sod. With a post hole auger they drilled a well and found water where the ranchmen told them there was none. With no trees to provide fuel for the stove, Sarah burned dried cow and sheep chips. They plowed and farmed and struggled to survive on the harsh plains, often with nothing to eat but jack rabbits and corn mush. When times were desperate, Will would travel into Brush to take temporary newspaper work.

Though life on the homestead was difficult, Harold was captivated by the immense beauty of the Plains. On clear days, he would climb the haystack and strain to see the Rockies, out of view many miles to the west. He hunted for arrowheads and collected bleached buffalo bones. He marveled at the endless miles of bluestem and buffalo grass. He spent many summer afternoons watching clouds float across an “indescribable blue of sky and distance.” In spring the Plains came alive with color; teal, mallard and canvasback ducks flocked to the small, temporary ponds created by spring rains and snow melt. Harold found barely visible buffalo and Indian trails stamped into the grass years ago, and an old road made by stagecoaches traveling across the Plains. In adulthood he recalled: “It was a raw, new land, most men said; but it was raw only in terms of Midwest farming, and it wasn’t new land at all–only the white settlers there were new. We were new and I, a boy to whom the whole world was new, gloried in discovery.”

In the spring of 1914 the Borland’s left the homestead and moved north to Brush. Will took a full-time position with The Brush Tribune, paid debts and saved. In April 1915 he quit the Tribune and moved his family south to the burgeoning Plains town of Flagler, CO, where he bought the weekly paper The Flagler News. In Flagler, Harold’s own newspaper career began when he learned the printing and editing trade from his immensely talented father. During his college years at the University of Colorado and Columbia School of Journalism in New York, Harold wrote articles for The Flagler News, while also working as a correspondent for The Denver Post, The Rocky Mountain News, The Brooklyn Times and Brooklyn Standard Union, United Press, and the weekly Kings Features magazine supplement “Home Journal.” After graduation from Columbia in June of 1923, Harold shortened his name to Hal, married classmate Helen LaVene and completed his first book, then spent 1924 and much of 1925 “barnstorming” through Utah, Nevada, California, Texas and North Carolina, working as a copy reader and linotype operator, while submitting short stories and poetry to magazines. Eventually he landed a position as night editor for The Asheville Citizen, before moving back to New York and working briefly for the Ivy Lee Publicity firm. In October 1925 Borland returned to Colorado and purchased the small weekly paper The Stratton Press, only a few miles from his hometown of Flagler.

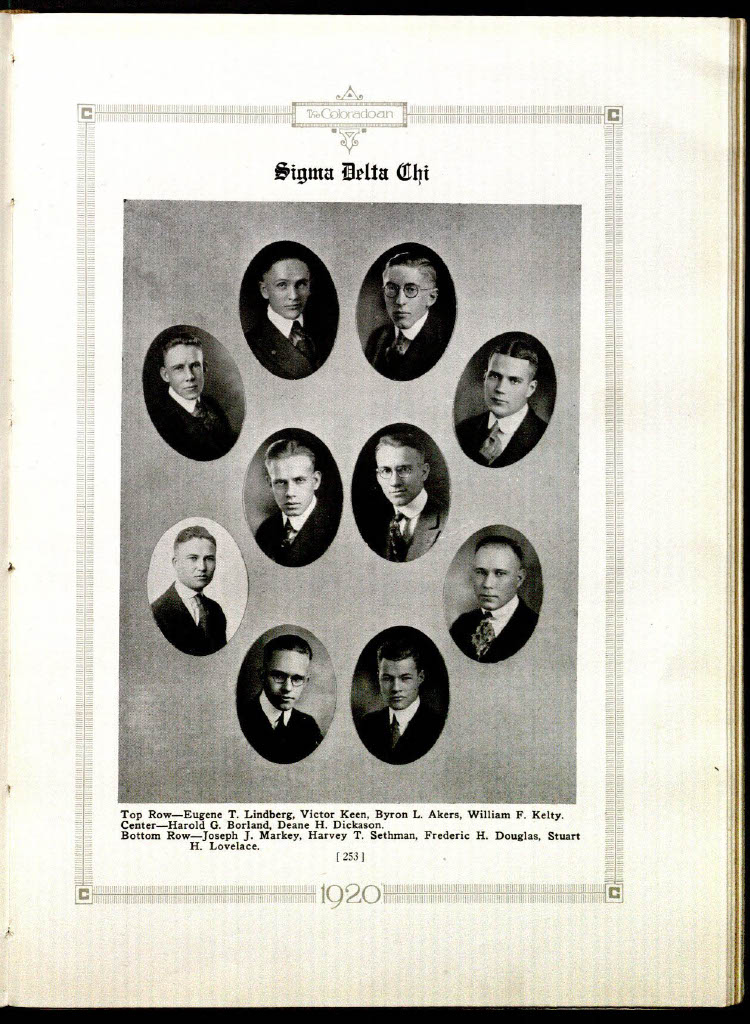

From the outset, Borland had an unwavering dedication to his work that he credited to his beloved father Will: “He gave me responsibility early, encouraged me to my own decisions, urged me to grow to the limits of my capacity.” This fierce drive to succeed was reinforced in June of 1920, when Harold and several classmates were suspended from the University of Colorado for their part in the publication of a laughably tame lampoon edition of the school newspaper, Silver and Gold. The edition had been approved by their journalism instructor, but when school officials took offense by the paper, the instructor denied any knowledge of the issue, leaving his students to shoulder the blame. Harold simply returned to Flagler without hesitation and poured his energies into his father’s paper. Borland never went back to UC, and years later reflected on UC President George Norlin’s foolish overreaction: “He expelled me from college for specious reasons at the age of 20, an act which drove the steel of resolution into my soul, to prove him wrong.”

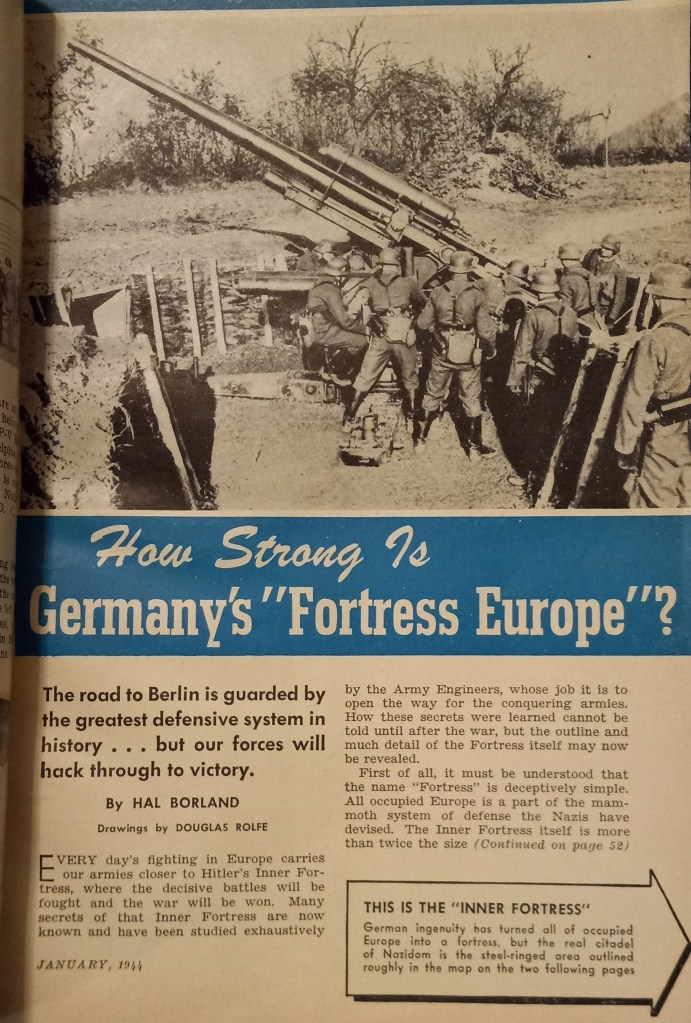

In the spring of 1926 Borland sold The Stratton Press and relocated to Helen’s hometown of Philadelphia. During the next eleven years working for Cyrus Curtis newspapers, Hal wrote over 1600 book reviews as well as several editorials a day for morning and evening editions of The Philadelphia Morning Sun and Evening Ledger. In 1937 he left the Ledger to write features for The New York Times Magazine. He stayed six years, reporting on everything from two World’s Fairs to allied war efforts during World War II. In the fall of 1941 Borland began a weekly nature column for the Sunday Times editorial page. From October 8, 1941 through February 21, 1978–the day before his death–nearly 1900 of his outdoor “editorials” appeared in the Times. In 1942 Borland published his sixth book, America is Americans, a collection of patriotic poetry inspired by Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor. During 1942 Hal also wrote scripts for the Government’s Office for Emergency Management radio program “Keep ’em Rolling,” a popular broadcast hosted by Clifton Fadiman that rallied support for troops serving overseas.

In the summer of 1943 Borland resigned the Times as a salaried employee to become a freelance writer, saying, “I left the Times because I wanted to write and they wanted to make me an executive. I left a good many jobs along the way for the same reason–that darned desk they wanted to put me behind! If they had kept me writing, I might have stayed.” He continued the Sunday nature editorials as a freelancer, scripted film documentaries on Navajo Indians, nature and geology, and wrote book reviews, short stories and features for Harper’s Magazine, The Saturday Evening Post, This Week, Holiday, Better Homes and Gardens, The Saturday Review and Readers Digest. Borland’s feature assignments would often take him on extended research journeys across the U.S., including a four month, 12,000-mile trip in the late summer and fall of 1945 for his post war report on America, “Sweet Land of Liberty.” During this trip, Hal and his second wife, writer Barbara Dodge, were married in Denver.

Hal and Barbara soon began collaborating on short fiction and novellas for McCall’s, Redbook and Colliers. The Borland’s used a tape recorder to capture their ideas, then each would work independently developing story lines. Whenever they bogged down on a piece, they would use a stream of consciousness technique over dinner, rapidly throwing out plot lines then choosing whichever seemed best. Hal took pride in never missing a deadline and stuck to a rigid schedule: “I get up between four and five in the morning and do practically all my reading then. For seven days a week, we’re at our typewriters by seven and keep at it until one o’clock or so.” By 1955 Borland had published over 350 articles and stories, both his own and those written with Barbara.

Borland was a frequent contributor to Audubon magazine, and collaborated on several books with Audubon editor Les Line. From October 1957 until his death in 1978, Borland wrote a 2500 word quarterly “reflective essay on the seasons as they come” for Morris Rubin’s magazine The Progressive. During this period, he also wrote the Wednesday “Our Berkshires” column for the Pittsfield, Massachusetts newspaper The Berkshire Eagle, and a weekly column for The Pittsburgh Press. The articles were primarily nature related, but also included politics, conservation issues, personal anecdotes, and critical pieces on Northeast Utilities and insecticides. Borland was a man of strong opinions who frequently used his columns to voice them. Borland was also a prolific letter writer, turning out hundreds of letters, typed and single spaced, and often three or four pages in length. And, in addition to his published books, Borland completed several more that never made it to print. An impressive amount of work, accomplished by simply making good use of his time.

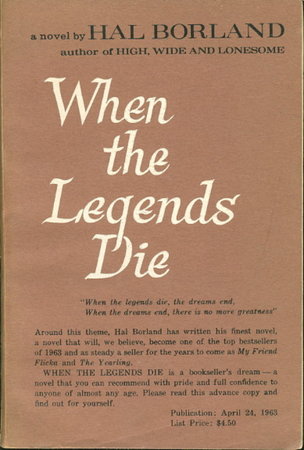

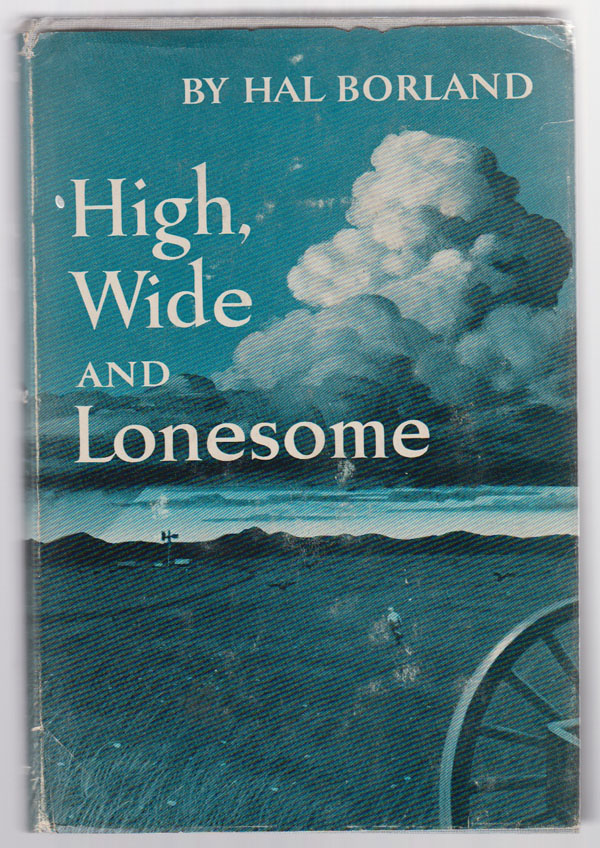

By the late 1950’s the magazine fiction market had cooled, and Hal decided to devote more time to writing books. In his Connecticut study Borland purposely sat with his back to the window to avoid distraction, saying, “The only way I know to get books written is to sit down at the typewriter and write, not wait for inspiration, whatever that is, and not spend the day staring out the window.” Between the publication of his superb Colorado homestead memoir High, Wide and Lonesome in 1956, and his death, Borland completed 29 books. By far, the most successful of these is his novel When the Legends Die, published by J.B. Lippincott Company on April 24, 1963. When the Legends Die is the beautifully written story of Thomas Black Bull, a Ute Indian boy born on the southern Colorado Reservation at Ignacio in 1907. When Thomas is three, he moves with his parents to Pagosa Springs where his father takes a job in the sawmill to pay a debt. When his father kills a man who repeatedly robbed him, the family flees to the mountains where they build a lodge and live in the old Indian ways. Thomas befriends a young grizzly bear cub and takes the name Bear’s Brother and is happy. But after a few years, Bear’s Brother is taken from the hills and sent back to the Reservation. He is again given the name Thomas Black Bull and forced to learn the white man’s ways. Thomas grows up to become a vicious bronco rider, all the while struggling to reclaim the happiness and peace he had as a child living in the mountains in the old ways of his Ute ancestors. As Hal described the book; “Tom is an Indian brought up by his mother in the ancient tribal ways. Suddenly he is plunged into the white man’s world. It’s like propelling a prehistoric man into the 20th century, and he finds that he can’t make the giant adjustment. To me, this is the tragedy of a man who grew up in the kindly, benevolent world of nature and suddenly found himself confronted by violence and brutality. How will he react? That’s how the story grew.”

In March of 1960 Borland completed the manuscript for his book The Dog Who Came to Stay and began planning for his next project. He had recently been offered a contract to write a nature book for Alfred A Knopf, and also had in mind a prequel to High, Wide and Lonesome, to be set in Nebraska in 1908, titled Country Editor’s Boy. Borland envisioned Country Editor’s Boy as the story of one childhood year in Sterling, with tales of his grandparents, friends and neighbors, “and through it will run the story of Old Phil.” While going through scrapbooks that spring, he rediscovered a short story he had written in 1938 called “The Years Are Round as the Aspens.” The story, which was set in Pagosa Springs and followed a Ute Indian boy who grows up to become a bronco rider, only to return to the hills in the end, was published in American Magazine in September 1939 with the title “Song of a Man.” When writing the story, Hal had drawn upon his own boyhood experiences in Pagosa Springs, where his father had taken a temporary editing job in 1911. That summer, eleven-year-old Harold and his father fished “in the swift white waters of the upper San Juan River” and the pristine water of Lost Lake. Harold hiked in the mountains, where he befriended old miners and loggers as well as local Ute Indians, eagerly absorbing their tales of the “old” way of life, listening to their tribal chants and learning bits of Ute language. After his graduation and marriage in June of 1923, Borland returned to the mountains of Pagosa Springs with Helen, where they camped while he completed writing his first book, a collection of thirty Native American myths and legends titled Rocky Mountain Tipi Tales. Hal made plans to someday build a cabin there, but that sadly never happened.

As Borland reread “Song of a Man” in 1960, he thought he might like to add new characters and rewrite the story as a full-length novel. In August he met with Lynn Carrick, his editor at Lippincott. Carrick very much liked The Dog Who Came to Stay (Borland’s fourth book with Lippincott) and asked Hal what he planned to do next. Hal told Carrick about his idea for the High, Wide and Lonesome prequel, and briefly mentioned an idea for a “book about an Indian boy, a bear cub and a rodeo background, the theme being a man’s inheritance.” Hal and Lynn had become good friends over the past four years and had an excellent working relationship. Borland was not fond of writing outlines; he would simply tell Lynn what he had in mind and Lippincott would draw up the contract. Carrick said he wanted to publish both books, and they agreed to go for the prequel first.

Three weeks before his meeting with Carrick, Borland had accepted the offer from Knopf for one book. It was not uncommon for Borland to be under contract with two publishers at the same time. He considered his “nature books” as separate from his fiction and autobiographical work, and preferred to have them published by a different company. Simon and Schuster had been Hal’s nature publisher, but he was unhappy with their indifferent promotion of his books. When the offer came from Knopf he “was ripe for a change” and signed the contract. Borland worked simultaneously on the Knopf book and Country Editor’s Boy for Lippincott for the remainder of 1960 and into March of 1961. He made steady progress on the Knopf book (Beyond Your Doorstep), but struggled with Country Editor’s Boy and set it aside. Hal concentrated his efforts on Beyond Your Doorstep and delivered his completed manuscript to Knopf in late spring. He then went back to Country Editor’s Boy, again with no luck, and on June 3 notified Carrick he was going to try the “Indian book” instead. Lynn readily agreed to the scheduling change and sent Borland the contract for the book, tentatively titled “The Indian,” in late June 1961 with a deadline of one year. On July 26, Hal sat down and easily wrote chapter one exactly as it would appear in the published book. (Note: When Country Editor’s Boy was eventually published in 1970, it was as a sequel to High, Wide and Lonesome, not a prequel).

In late August Lynn Carrick was relocated to London and George Stevens, a Vice-President at Lippincott, became Hal’s editor. Borland told George that “The Indian” was progressing ahead of schedule, and they decided to move the deadline up to early 1962 with publication in the fall. The project was soon sidelined, however, when Barbara’s aged mother in Waterbury, Connecticut suffered a heart attack at the same time Hal’s mother in Nebraska fell and broke her hip. Trips between Waterbury and Nebraska took up all of November and December, and it was not until January 1962 when Hal returned to work in earnest. In early January he quickly wrote the short children’s book The Youngest Shepherd, then started back full time on “The Indian.” By the 21st of January, progress on the book had stalled, and a determined Borland wrote George a “conscious letter,” where he said, “I have been pushing at The Indian because of my pride in meeting deadlines. . . .I know you told me there was no pressure from you. I appreciate that. I have generated my own pressure; and now I am going to stop pressing and finish the book in its own time.”

For the next six and a half months, seven days a week, he worked on the book, revising some sections as many as six times before he was satisfied. The character “Mary Redmond” gave Borland a great deal of difficulty and had to be rewritten over a dozen times. On August 2 Borland was optimistic the book was nearly complete and sent a progress report to George. He wrote, “This draft is finished. . . .and I hope and pray that it is substantially final. Barbara will read it next week, and I will read it through, and we will pool reactions. . . .You know the varied feelings one gets when a script is apparently done and yet may have holes, the feeling of hope and wonder and mixed satisfaction.”

To his disappointment, Hal and Barbara readily agreed the final section was weak, so he began revising again. On September 17, Borland completed his rewrite and mailed the manuscript to Lippincott, one of the few instances he delivered a piece after its deadline had passed. George enthusiastically read the work, declared it “stunning,” and congratulated Borland on a “distinguished and most interesting job. You have brought off your central character magnificently. . . .and the narrative is handled expertly.” He offered a few minor changes and suggested it be titled When the Legends Die, from an unpublished Borland poem being used as the epigraph. Borland made the revisions, and on October 27, 1962, mailed the final manuscript to Lippincott.

Throughout these hectic months Borland never missed a single Times editorial or Progressive or “Our Berkshires” column, a testament to his years as a newspaperman in Philadelphia and New York. For his October 31 Berkshire Eagle column–four days after completing When the Legends Die–Hal wrote a scathing piece titled “The Sad Case of John Steinbeck.” It had recently been announced that Steinbeck would be the recipient of the 1962 Nobel Prize for Literature, an award Borland clearly felt Steinbeck did not deserve. In the article Borland railed, “for the life of me I can’t understand this award,” and called the awards committee “incredibly stupid” for choosing Steinbeck over more deserving authors such as Robert Frost. He went on to call Steinbeck’s The Winter of Our Discontent “one of the most haphazard and unimportant novels he ever wrote. . . .almost a travesty on the serious novel and one that went to pieces in the end, as though Steinbeck got tired of what he was doing and just slapped things to any kind of conclusion.” Borland pegged The Grapes of Wrath “a period piece. . . .a good novel, but it dealt with a passing situation and actually lacked any profound statement on the condition of man. Read it now and you wonder what all the shooting was about.” He complimented Steinbeck on Of Mice and Men, saying it was “one of the best pieces of sustained writing he ever did,” but concluded “its importance is debatable.” He called Cannery Row “an uneven book of slight importance either as literature or social comment,” and tagged The Wayward Bus “a pretentious piece of trash that made even his friends wonder what had happened to Steinbeck.” Borland dismissed East of Eden, saying “his writing was diffuse and uneven, his viewpoint uncertain,” and declared Travels with Charley “full of cliches both of words and thoughts, a hack job done for magazine publication and put between covers as a book.” Borland referenced an interview that Steinbeck had recently given to The New York Times, where Steinbeck himself said he did not feel he deserved the award. Borland summed up Steinbeck’s work by saying, “there are two or three better than average novels and there are maybe half a dozen excellent short stories,” but concluded “there is no real, coherent body of Steinbeck work. . . .as a social commentator he has been inconsistent, and as a writer he has turned out some miserable prose as well as some vivid, meaningful words.”

Meanwhile, George Stevens was thrilled with When the Legends Die and was wasting no time getting it into print. Stevens had been instrumental in Lippincott’s publishing of Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird in 1960, and promised to give Borland the same intense promotion they had given Lee and her masterpiece. In late December Lippincott sent Borland page proofs of the book, which he read immediately and mailed back on the 31st. Hal also sent an emotional letter to George, where he beautifully recalled an experience he and Barbara had at Mesa Verde National Park several years earlier. Hal was there to give a speech to a woman’s club, and one evening a group of teenaged Navajo boys put on a fireside demonstration of ancient chants. Hal wrote, “They chanted, and the songs had the mystery, the wonder, the sadness and exultation of that old country. . . .The feeling was deep and primary, elemental. The audience was rapt, silent; then several of the women began to cry.” When the demonstration was over, “It was several minutes before the audience roused and left the hillside, in twos and threes and in silence.” Hal recalled how he and Barbara gathered pinon nuts the next day, which gave them a feeling of kinship with the ancient Native American custom. These events are the basis for Borland’s dedication in When the Legends Die, which reads; “For Barbara, Who has gathered pinon nuts and heard the old songs in the firelight.” Hal reflected on Legends, saying, “Who knows when a book really takes root, or where, or from what seed. . . .I came out with the feeling that I came fairly close to where I wanted to, and I suppose that’s something.”

The January 1963 Lippincott Spring Catalog listed When the Legends Die with an April 24 release date. Four hundred and fifty paperbound review copies were sent to selected booksellers and reviewers throughout the country and the response was immediate. Advance orders quickly reached 14,000, and Legends went into a second printing two months before its scheduled publication date. Borland was about to have the first bona fide smash of his career when tragedy struck. On March 13, 1963, his oldest son, Hal Jr., died suddenly from a massive heart attack in Oswego, New York. He was only 38. Hal and Barbara traveled to Oswego where they spent the next several days burying his son. This was the second child Borland had lost. His youngest son Neil had passed away at age sixteen on December 31, 1945.

Borland was badly shaken and did the only thing he really could do, which was to return to work. He turned in his weekly columns, contemplated his next project, and anxiously awaited the publication of When the Legends Die. But not even his recent loss could dampen Hal’s excitement. He wrote George; “Right now I feel a little like Tom letting himself down into the saddle on a bronc in the chute, waiting for the gate to open on pub day. It looks as though we’re going to put on a show, and I don’t see how the bronc can fail to live up to his billing. It could be quite a ride.” In early April, Borland made a rare trip from his northwestern Connecticut farm into New York City for promotional interviews, and by mid-month Legends was in its third printing with advance orders over 25,000.

When Legends was released on the 24th, its reception far exceeded Lippincott’s expectations. Reviews were overwhelmingly positive, with Borland universally praised for his writing style and sympathetic treatment of his characters. Saturday Review called the book “. . .a warm, human story told with effective simplicity.” The Wall Street Journal said When the Legends Die was “. . .good reading on many counts; a book of beauty and lofty spirit, warmly recommended.” The New York Herald Tribune complimented Borland on a “. . .tremendously moving story. . .Hal Borland tells the story simply, with the authority of a master.” The Hartford Courant Magazine offered perhaps the most gratifying praise: “Hal Borland. as always, writes with an intimacy of the west and its people and his empathy for the Utes is reflected in every page. . . .For the first time in my memory, the Indian becomes a credible human creature with resourcefulness, tenderness and considerable nobility.” Sales of When the Legends Die were strong from the start, and Borland soon found himself on best seller lists across the country.

When the Legends Die turned up on many lists in 1963, though not all gave Borland cause for celebration. The American Booksellers Association chose When the Legends Die as one of eleven books of fiction given to the White House Family Library that year, and included it in their selection of 105 books “that will be given to the chiefs of state of 100 countries.” Also on the list was Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird, Carson McCullers’ Clock Without Hands, and Travels with Charley and The Winter of Our Discontent by John Steinbeck. (“I rather like the company there, with only a few exceptions, which I shall not list”). When the Legends Die was considered for the Pulitzer Prize for fiction in 1963 but did not win. (The award went to William Faulkner for The Reivers). Over the next few years, Borland occasionally expressed his frustration with the volatile political forces influencing award committee’s decisions in the early 1960’s. In a May 10, 1964 letter to George Stevens he wrote: “I’d rather not talk about the Pulitzer Prizes. I still burn at the obvious search for special pleading or for authors whose chief distinction is the color of their skin. I had thought those were awards for literary merit, not for propaganda or topical yawps.” On March 20, 1966, Borland wrote a heartfelt letter to his close friend, naturalist Peter Farb, revealing his disappointment still ran deep: “I seem to grow more self critical. . . .You just do what you can, the best you can, and sometimes you hit it right. . . .Legends took off and still is doing well, with unexpected rewards still coming. It even had a toe-hold on the Pulitzer, but didn’t make it because Tom Black Bull was red instead of black in a year when, I have been told, color was a vital factor. How the hell would I know ahead of time? In any case, he had to be what he was. Maybe some of the boys can write for the big money, but some of us can’t, too, because we have to live with ourselves.”

His bitterness over the Pulitzer notwithstanding, Borland never needed to doubt what he had accomplished with his book, or the impact it would have on his readers. When the Legends Die quickly became a mainstay on junior high and high school required reading lists across the country and remains so to this day. The book was, not surprisingly, enthusiastically embraced by the Native American community. For the remainder of his life, Borland regularly received gracious letters from young students, many Native American, who were deeply moved by the book. Letters were often addressed to “Thomas Black Bull,” and told of the profound impact the story had on them. Hal personally answered every letter, often including words of advice and encouragement for the student’s future studies. The letters continued to arrive even after Borland had passed away. In March of 1978 Barbara received a package of letters from a ninth grade English teacher at a reservation school in Wellpinit, WA. He told of how difficult it had been for him to interest his students in basic English until they read When the Legends Die. All of them identified with young Tom Black Bull, and honestly expressed their feelings in their letters to Borland. One youngster wrote, “Myself, I would have up and left into the mountains and found my Bear Brother and gone where no one could find me. Tom, why did you let them push you around and tell you to do this and that? I could not stand to be pushed around or told what to eat, how to dress, and all those things. I feel kind of sorry for you, but you may teach your children the old ways one of these days.”

Borland occasionally gave lectures to English classes, where he cautioned students on the futility of over-analyzing his, or any, book, which only leads to finding false meanings. When writing Legends, Borland aimed for “a kind of semi-poetic job. . .maybe with overtones of meaning,” but was careful that any symbolism”not be labored.” After one lecture in 1966, Hal wrote George Stevens, “Part of my job, of course, was setting them straight on this symbolism thing, which teachers and critics dream up, and also telling them that detailed analysis of writing is a bootless exercise–it’s like taking a watch apart to find the tick; all you get is a lot of little wheels, and no tick.”

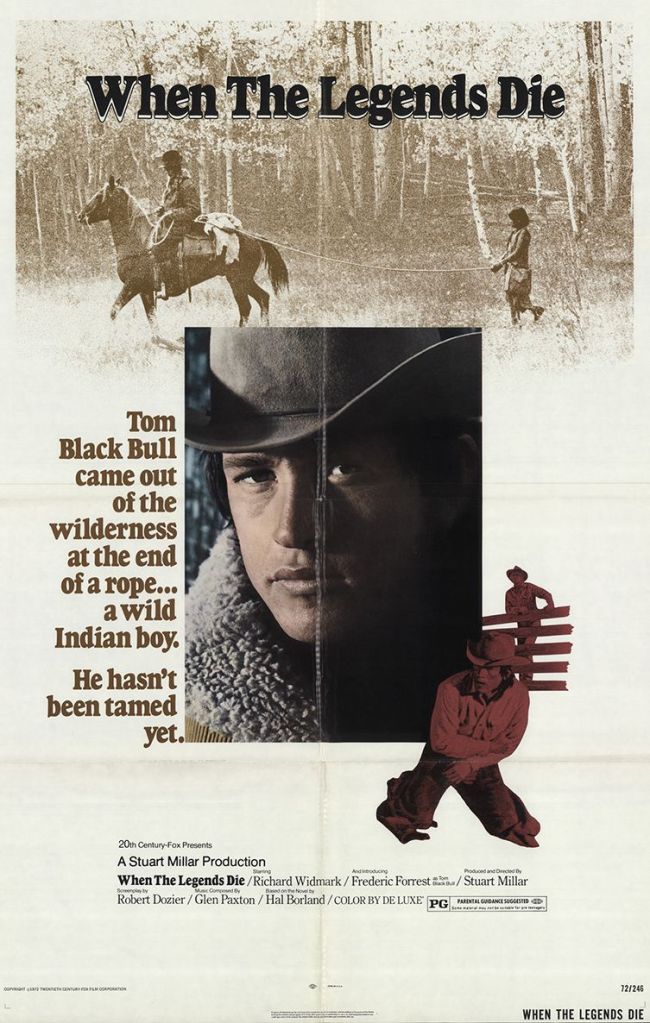

In 1966 Borland sold the film and television rights to When the Legend Die to Hollywood producer Stuart Millar and Embassy Pictures for $30,000. Millar was determined to direct the film himself and offered Borland a screenwriting position, which he turned down. Over the next five years, Millar declined several opportunities to produce the film with established directors. His persistence paid off in 1971 when 20th Century Fox agreed to finance the film with Millar producing and directing. Veteran screen actor Richard Widmark was cast in a leading role as the character Red Dillon. Widmark traveled from his home in Roxbury, CT to Borland’s farm in Salisbury, where they spent an August afternoon discussing the book. Filming was done in September and October 1971 in Durango, Colorado, and the Ute Reservation in Ignacio, the exact site Borland wrote about in the novel. The adult Thomas Black Bull was played by newcomer Frederick Forrest in his first starring role. For the role of Bear’s Brother, Millar cast a young Ute Indian boy named Tilman Box. In early December, Millar sent Borland a group of stills and Borland was completely taken by Tilman Box. Hal immediately wrote to the young actor: “I almost called you Bear’s Brother, because I just saw the picture of you in the Southern Ute Drum. In those two pictures, the ones with the bear, you clearly are the boy I was writing about. . . .I can’t think of a better choice for that role than you are. . . .you have already. . . .made my boy come true. Thank you.”

When the Legends Die has been published in the U.S., Britain, Canada, Germany, Italy, France, Spain, Norway, Japan, Holland, Portugal, Australia, Switzerland and Sweden. It has been featured in book clubs around the world. Millions of specially bound editions have been shipped to junior high and high school English classes since the 1960’s. But exactly how many millions of copies Legends has sold seems to be anyone’s guess. J.B. Lippincott Co. was purchased by Harper and Row in the late 1970’s, and Lippincott sales records have apparently vanished in company mergers and computer system changes over the years. However, Legends went through at least thirteen hardcover printings, and Lippincott was delivering new printings as late as the spring of 1975. The first Bantam Books paperback edition appeared in the late summer of 1964. By November 1972 paperback sales had passed 800,000. Bantam, Bantam Pathfinder and Starfire, and Laurel Leaf paperbacks remained in continuous printings until January of 2012. A 2001 Publishers Weekly list of All Time Bestselling Children’s Books (Volume 248, Issue 51, 12/17/2001) ranked When the Legends Die at #46, and put paperback sales from 1984 to 2001 at 3,353,965. Bantam paperback sales info from 1972 to 1984, and 2001 to 2012, appears to be lost or inaccessible. In November 2011, Open Road Media (openroadmedia.com) began offering electronic editions of When the Legends Die, as well as Borland’s High, Wide and Lonesome, and The Dog Who Came to Stay. Open Road has since added Beyond Your Doorstep, Country Editor’s Boy, Penny and This Hill, This Valley to their Borland titles. In late 2019, Echo Point Books & Media issued new hardcover and paperback editions of When the Legends Die, The Dog Who Came to Stay, Book of Days, Twelve Moons of the Year, Sundial of the Seasons and High, Wide and Lonesome. Though accurate sales figures are elusive, one thing is certain: since its publication in April of 1963, When the Legends Die has never been out of print.

In When the Legends Die, the young boy Bear’s Brother is tricked into leaving the mountains by Blue Elk, an elderly Ute who betrays his people to the reservation for money. Blue Elk tracks Bear’s Brother deep in the mountains by summoning distant memories of when he was young and lived in the mountains in the old ways. He tells the boy that he must come back to Ignacio to sing the old songs to his people, and tell them of the old ways so they would never forget. At the reservation, Bear’s Brother quickly realizes he has been lied to and that he will not tell of the old ways, but will be forced by the white men to learn the new ways instead. Borland described the dilemma as “the story of an American Indian who is stripped of his heritage and traditions, loses his identity with his own self, becomes a man obsessed with violence, and eventually returns to the peace and understanding of his own background.” In August of 1968, Borland received a letter from Dr. Robert Bergman, a psychiatric consultant for the Navajo Division of Indian Health in Arizona. Bergman talked of how he used When the Legends Die in a training course for staff members in Native American boarding schools. The participants in the course, many of Ute ancestry, were all former reservation students themselves and were brought to tears by the book, which reminded them of their own childhood experiences. A grateful Borland wrote Bergman that his letter was “tremendously satisfying” and “pleases me more than I can say,” and added, “Your report about the reception of my novel, When the Legends Die, among the Indian people and those working closely with them makes me feel very proud. I somehow feel that at last Tom Black Bull has been able to tell some of the old tales and sing some of the old songs to his own people, to help make them understand and take pride in their unique heritage.”

Copyright 2014. Kevin Godburn. All Rights Reserved.

Waldo Bailey, Hal Borland, and Bartholomew’s Cobble

In 1890 a thirty-one-year-old Massachusetts landscape architect named Charles Eliot recognized the need for an organization to protect and maintain natural locations throughout his home state. Eliot founded The Trustees of Public Reservations* (the nation’s first land trust) the following year to “preserve, for public use and enjoyment, properties of exceptional scenic, historic, and ecological value throughout Massachusetts.” The Trustees, a nonprofit, charitable corporation that relies on private donations, memberships and occasional public grants, obtains land through gift or purchase and currently owns, manages and protects 122 reservations covering more than 27,000 acres.

*(The group shortened their name to The Trustees of Reservations in 1954).

Bartholomew’s Cobble, a 357-acre reserve located in the village of Ashley Falls (town of Sheffield) in the southwest corner of Massachusetts, less than one mile north of the Connecticut border, was acquired by the Trustees in 1946 when the Garden Club of America, and “conservation-minded individuals,” donated funds to purchase 44 acres from then-owner George Bartholomew. The Cobble grew to its current expanse through subsequent donations and purchases of land, including the December 1969 purchase (for $67,500) of 115 acres known as Hurlburt’s Hill, one of the Cobble’s most popular attractions with its magnificent views of the Berkshires and Upper Housatonic River Valley.

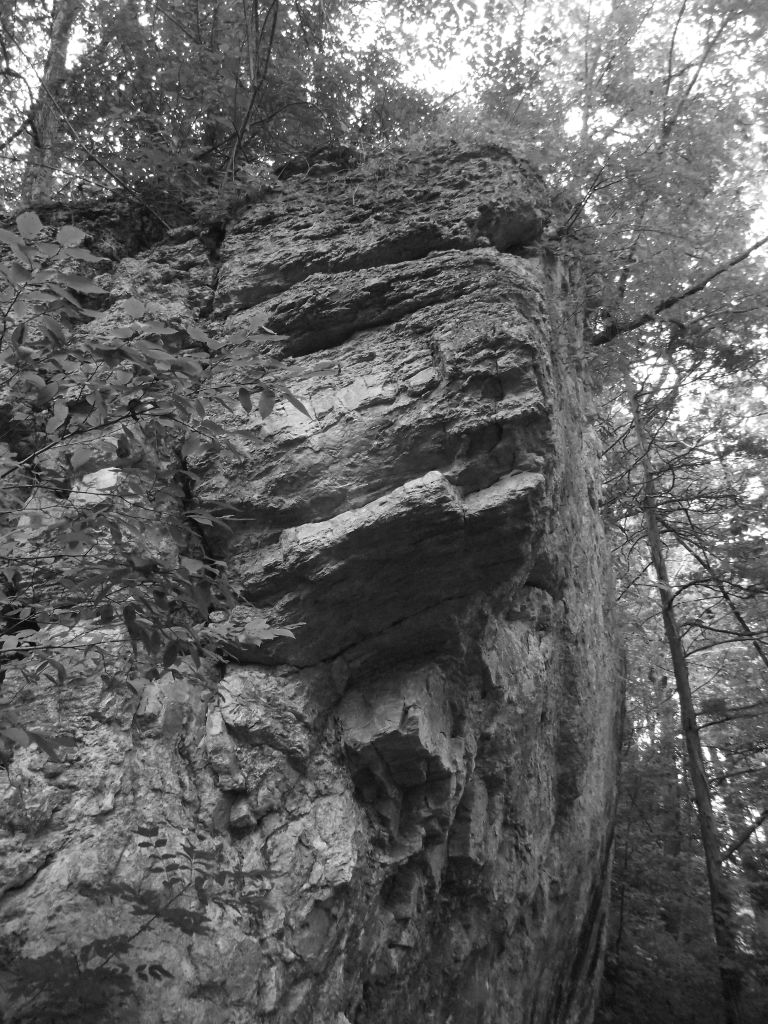

The Cobble is centered by two massive limestone knolls–the north and south cobbles–and bordered by the Housatonic River, woodlands and open meadows. The bedrock of the Cobble is composed of quartzite (metamorphosed sandstone), and marble (metamorphosed limestone), formed by heat and pressure while buried under other rock far below the earth’s surface, and “foldings” of the earth’s crust. (This transformation from limestone to marble “involves a recrystallization of the material and not a change in composition;” it is chemically still limestone). Some four to five-hundred million years ago the Taconic Mountains were formed by a folding, the “Taconic Disturbance.” Another folding, the “Appalachian Revolution,” occurred about 200 million years ago and the Appalachians were formed. Millions of years of erosion, as well as the geologically recent scraping from retreating ice, have worn away the deep rock that once covered the region, giving the Upper Housatonic River Valley and surrounding Berkshires their present, elegantly rounded, beautifully quiet shape.

The marble of the Cobble contains the mineral tremolite, making it more resilient to the effects of erosion, causing the Cobble to “rise” above the surrounding fields and river. The fertile soil of the Cobble supports a diverse collection of ferns, grasses, wildflowers and trees; more than 800 plant species have been identified and catalogued. The Cobble is also a favored nesting stop for more than 250 bird species. Botanists, geologists and ornithologists the world over have traveled to study the unique array of life at the Cobble, and, in 1971, the U.S. Department of the Interior/National Park Service named the Cobble a National Natural Landmark. But perhaps the most enduring legacy of Bartholomew’s Cobble is the peace found by those who regularly walk its trails, marvel at the majesty of the Berkshires from the summit of Hurlburt’s Hill, and silently contemplate the slow-moving Housatonic River. For many, the Cobble is a fundamental element in their life, a necessary stop in their daily routine. The Cobble repays this loyalty with unexpected wonder and surprise. During early August of 2021, the Cobble was visited by a young Roseate Spoonbill, a Florida wading bird that had never been observed in Berkshire County before. Birders from Vermont, New Hampshire, Maine and Boston made daily trips to Ashley Falls, hoping for a sighting of the historic visitor. The Spoonbill, which may have been lured north by an unusually rainy and humid summer, made itself at home among a group of Egrets, spending a week feeding in the flooded farmland before disappearing for home. (A terrific cover story on Spoonbills in the winter 2022 issue of Audubon magazine cites climate change and more than a century of ill-advised government policies as the causes for this unprecedented behavior. Spoonbills feed in shallow, fresh water. As sea levels continue to rise, salt water intrudes farther inland and Spoonbills’ nesting grounds are gradually shifting north).

In a beautiful stretch, the Housatonic River winds peacefully through the fields of the Cobble, serving as a landing strip for the hundreds of geese that fly in every day at dusk. You hear them honking in the distance, heading for home. Soon the sky is full of V-shaped formations, flying in from all directions like squadrons of B-17 bombers returning to base in the World War II film Twelve O’Clock High. You can almost picture Gregory Peck standing on the riverbank, anxiously searching the sky and counting returning airplanes. The geese circle the river in a perfectly choreographed dance. There are so many of them you expect them to collide in a tangled heap, but they never do. They sweep in, circle a couple of times, then, with their webbed landing gear extended, glide over the water to a graceful landing. Soon the river is full of geese; there does not seem to be any room for more, yet they keep arriving. Somehow, they all touch down beautifully without a single mishap.

On nights when the moon is full or nearly full, you can look across the fields of the Cobble, the trees clearly visible and casting shadows as if it was just before dusk. The Berkshires to the north and Canaan Mountain to the south are in plain view. Even without the moon the stars cast enough light to safely find your way on foot. Jets bound to and from New York and Windsor Locks carve tic-tac-toe boards in the sky with their flashing lights. Airplanes seem to fly at lower altitudes at night for some reason. On humid summer nights the orange moon-rise is more than I can even describe. Mist rises from the fields and builds into drifting banks of fog. I have stood at the edge of the fields and watched a wandering wall of fog move eerily toward me until I was surrounded, damp from the dew and shivering and loving every second of it. Only once, though, have I seen a meteor–wouldn’t mind seeing a few more of those.

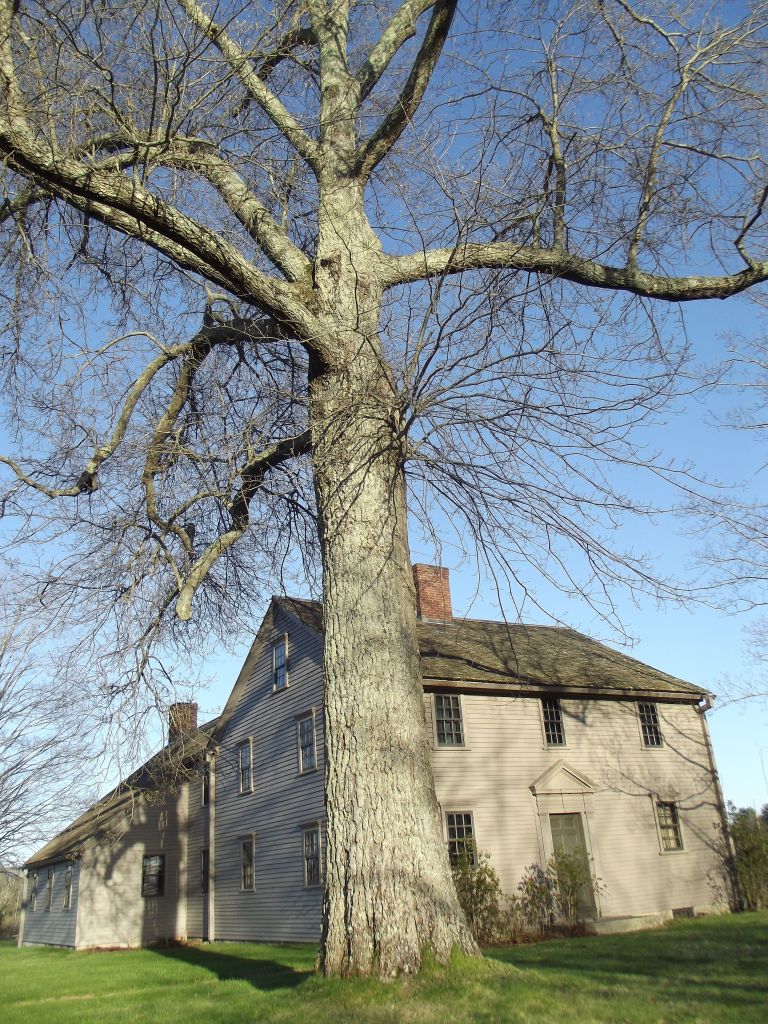

On April 25, 1724, Captain John Ashley was one of four Englishmen that “purchased” an immense tract of land in southwestern Massachusetts, more than ten miles wide and extending twenty miles north from the present day Connecticut border, from native Mohican tribes for “460 pounds in money, 3 barrels of cider and 30 quarts of rum.” The town of Sheffield, in the southwestern corner of that tract, incorporated on June 22, 1733, the first town in Berkshire County to do so. Ashley’s son, an attorney also named John, settled in Sheffield in 1732. Ashley rose to the rank of Colonel and led an attachment in the French and Indian War, served as a judge and selectman, and played a dominant role in expanding settlement and industry in Sheffield. The village of Ashley Falls is named for Colonel John Ashley.

Colonel Ashley married Hannah Hogeboom from Claverack, New York, and, in 1735, built their home along the west bank of the Housatonic River near present day Rannopo Road. The Ashley House served as a hub of 18th-century political discussion and activity in Sheffield. In January of 1773, Ashley and a committee of citizens drafted “The Sheffield Declaration” in the Ashley House, a series of resolves proclaiming “that mankind in a state of nature are equal, free, and independent of each other,” and asserting their independence from British rule. The Sheffield Declaration was published in February, preceding The Declaration of Independence by more than three years.

A family friend described Colonel Ashley as a kind and gentle man, but wrote of Hannah as “a shrew untamable” and “the most despotic of mistresses.” Despite his belief in individual freedom, Colonel Ashley was the largest slave owner in Sheffield. “Mum Bett,” one of Ashley’s five adult slaves, was born in the early 1740s and had been a slave in the Hogeboom house as a child. Mum Bett fled the Ashley home in 1780 after a physical altercation with Hannah and inspired by overhearing discussions of The Sheffield Declaration and the recently enacted Massachusetts Constitution. Mum Bett walked to the home of Theodore Sedgwick, a Sheffield attorney and friend of Ashley’s, and a member of the Sheffield Declaration committee. In August of 1781, at the County Court of Common Pleas in Great Barrington, Sedgwick argued for Mum Bett’s freedom based on the Massachusetts Constitution, winning the case and setting a precedent for the abolition of slavery in Massachusetts. Mum Bett adopted the name “Elizabeth Freeman,” and passed away on December 28, 1829. Colonel Ashley died in 1802 at the age of 92.

After Colonel Ashley’s death, the vast Ashley land holdings were divided among children and grandchildren and eventually sold. The Ashley House had several private owners during the 19th and early 20th-century. Wyllis Bartholomew purchased the house in 1838 and left it to his son Hiram in 1846. Hiram then sold it to his son George in 1852. (The Bartholomew’s also began purchasing large tracts of land from the Ashley family). George A. Brewer purchased the home and 220 acres in 1882 and ran the property as the Eureka Stock Farm. Harry N. Brigham, a great-great-grandson of Colonel Ashley, purchased the house in 1930 and moved it a short distance to its present location on Cooper Hill Road. Brigham and his wife Mary added a small addition to the house as living quarters, and displayed their collections of antiques and pottery in the Ashley House. Edward Brewer and his wife purchased the house in 1945. Brewer had lived in the house as a child when it was owned by his father. The Brewer’s supplemented the Brigham collection with antique household items and farming equipment.

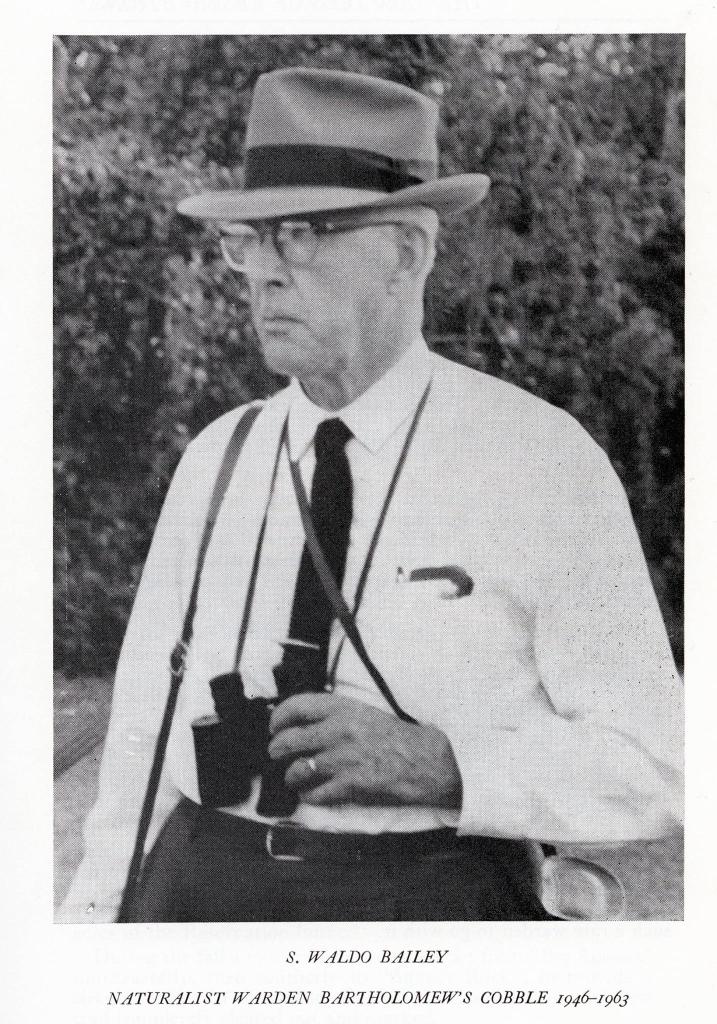

Soon after the Trustees purchased the Cobble from the Bartholomew family in 1946, Waldo Bailey was hired as the reservations’ first Warden. S. Waldo Bailey was born July 10, 1885 in West Newbury, Massachusetts. At an early age, Bailey developed a keen interest in nature and birds in particular. Using the scarce books available at the time, Bailey immersed himself in the study and observation of birds and the natural world that surrounded him. Bailey also indulged his passion for Native American folklore, hunting for arrowheads and Indian relics on his frequent field trips in Essex–and, later, Berkshire–Counties.

In 1902, at age 17, Bailey began documenting his discoveries in his journals. Over the next sixty years Bailey created a remarkable record, more than 4,000 pages long, of bird sightings and migrations–complete with intricate charts of monthly and annual bird counts, detailed observations on plant-life, wildflowers and weather patterns, inventories and drawings of the arrowheads and Indian artifacts that he seemed to instinctively find with little effort, travel dates and locations, as well as his endlessly engaging personal thoughts and insights on all he had seen. Bailey’s journals reveal a man deeply committed to his life’s work, a passionate observer who never faltered in his search for knowledge. Before he reached the age of thirty he had published several articles in The Auk, an ornithological magazine established in 1884. Bailey was also an exceptional photographer and early proponent of color photography in the 1920s. Bailey’s superb photographic work is second only to the awesome achievement of his journals.

Bailey moved to Pittsfield, Massachusetts in 1916, supporting his family with an unlikely position as a cost accountant for the General Electric Company, while continuing his field trips throughout Berkshire County. During the 1920s, Bailey taught a nature appreciation course at Pittsfield High School, and offered traveling lectures on nature, ornithology and photography. Bailey left GE when the Great Depression hit and spent the next several years working for the National Park Service, as well as a supervisor in the Berkshire County Civilian Conservation Corps, while continuing to publish articles, lecture and teach. Bailey was a member of many ornithological societies and committees, and served as president of the Hoffmann Bird Club, a Berkshire County group formed in 1940 and named for Ralph Hoffmann, a friend and field trip companion of Bailey’s, and the author of A Guide to the Birds of New England and Eastern New York (1904). After leaving the Park Service, Bailey was hired as Warden for the Lenox Bird and Wildflower Sanctuary (Massachusetts Audubon Society), a position he held until April of 1946.

Bailey was good friends with a Pittsfield resident named Rene Wendell. Though 31 years his junior, Wendell shared Bailey’s love of nature and enthusiasm for Native American artifacts. “R.W.” is mentioned often in Bailey’s journals as a companion on arrowhead hunting trips to favorite locations in Stockport and Schaghticoke, New York, among others. Wendell’s son, Rene Jr., served as the Cobble’s Warden from 2002 to 2015. In 2014, Rene (pronounced “Rennie”) built a cabin-style screened deck overlooking the Housatonic River. Visitors to the Cobble are invited to sit and read their favorite nature writing, record thoughts and observations in their journals, or simply have a snack and enjoy the view. The beautiful deck is one of Rene’s many outstanding accomplishments during his tenure at the Cobble.

The observations recorded in Bailey’s journals are far too numerous to try to summarize here, but two in particular merit a mention. On September 20, 1953, Bailey wrote that “A party from the American Museum of Natural History, of New York, visit the Cobble,” a group that included Miss Farida A. Wiley. See my article “Anatomy of an Award” for more on Miss Wiley and the role she would play in Hal Borland’s life in 1967 and 1968. Two days later Bailey wrote, “Astronomically Autumn enters at 4:23 A.M. Our brief Summer is over, yet the Autumn brings balmy days, and from year to year seems to loiter later than formerly. Is our season actually changing, as the rapid recession of the glaciers in the Northern Hemisphere might indicate? It’s doubtless too slow an evolvement for a single lifetime to register.”

Hal and Barbara Borland purchased their farm along the bank of the Housatonic River on Weatogue Road–two miles south of the Cobble–from Nelson Case on July 26, 1952. The Borland’s had been living on Rock Rimmon Road in Stamford, CT, making frequent trips about the country for Borland’s freelance magazine and newspaper work. But a serious illness in February of 1952 caused Borland to reevaluate his life and future. Borland wrote of the event in his 1957 book This Hill, This Valley:

“Five years ago I was taken to a hospital and partook of a miracle. I went there dying of a ruptured appendix and advanced peritonitis, and I came back alive. I went there while Winter was passing. . . .I came back to March. . . .March and I were alive, getting acquainted with each other all over again. . . .

“March passed, Spring strengthened, and I knew that I, too, had come to a new season in my life. Almost half my life had been spent in a daily job, a good part of it at a desk in a city. Because of some urgency in myself, I had lived most of those years at the edge of the country, near woods and open fields. I spent evenings and weekends there. . . .

“All that time I had made occasion, at least once a week, to renew my acquaintance with the trees and flowers, the weather and the wind. However, I felt the need to remain close to the city, never more than an hour away. The habit was deeply ingrained, and though I compromised by owning a few acres of hillside and brook and coming to know them intimately, I was being trapped by suburbanization. . . .

“Then I went to the hospital and came back, and it all seemed more of a compromise than a man should make. Reappraisal was inevitable. Barbara, who is my wife and who had known that I would come back when others doubted, agreed that there were things more important than an assignment in Maine or Tennessee. . . .So we sold our suburban acres and moved to Weatogue, to live, to write, to see and feel and understand a hillside, a river bank, a woodland and a valley pasture.

“We came here, not to a cabin in the wilderness but to a farmhouse beside a river. So far as the legalities are concerned, we bought and own a hundred acres, one whole side of a mountain and half a mile of river bank. I have spent the months and years since, living with this small fraction of the universe and trying to know its meaning–to own it, that is, in terms of observation and understanding.”

It did not take long for Borland to find his way to the Cobble and Waldo Bailey. The two became close friends, often spending afternoons sitting on the porch of the Warden’s cabin, walking the fields of the Cobble, and hunting for arrowheads. On May 28, 1958, Borland began his weekly “Our Berkshires” column for the Pittsfield, Massachusetts newspaper The Berkshire Eagle, the start of a twenty year run with the exception of a three year break between April 1968 and August of 1971. Borland’s first column featured the Housatonic River, setting a precedent for the many columns he would devote to the river, Ashley Falls, the Cobble and Waldo Bailey, including his August 6, 1958 column “The Cobble”s Waldo Bailey:”

“I don’t know how S. Waldo Bailey happened to be chosen as warden of Bartholomew’s Cobble, and I doubt if anyone really knows. But I have a theory about such natural oases and the people who shape their public character, and it fits this occasion. Any reservation is the result of the work and determination of a few people, and when it comes into being it picks its own warden by a kind of mutual process of elimination. That, regardless of the details, is how Waldo Bailey came to the Cobble. The Cobble needed him, and he needed the Cobble.

“. . . .He has lived in Berkshire County 42 years, still lives in Pittsfield. After he quit the accounting office he spent a time in the forest service. Then, 12 years ago when the Cobble was established, he became the first warden. He is the only warden the Cobble has had. He has probably been host to at least 20,000 visitors there.

“As we sat and talked the other day at the warden’s cottage, Waldo Bailey looked more like a conservative, middle-aged businessman than an outdoorsman. He wore a white shirt and tie. His hat was a gray fedora. He wore low, rubber-soled shoes. He smoked cigars. But his mind ranged back to Indian arrowheads on the boyhood farm, to the smell of salt marsh, to snowshoe trips up Greylock in 28-below-zero weather, to conservation policies and slipshod lumbering, to stream pollution, to the Cobble’s history.

“. . . .If Waldo Bailey didn’t love the Cobble he wouldn’t drive 60-odd miles every day from April till November to watch over it, cherish it, share it with 2,000 visitors every year.”

Bailey was mentioned frequently in Borland’s column, often in articles titled “Notes from the Daybook” and “Interlude at the Cobble.” In one, Borland wrote, “If I hadn’t seen the cardinal I probably wouldn’t have stopped. I was driving up the back road and slowed down at Bartholomew’s Cobble, as always, and on the ground under a cedar just beyond the entrance was this cock cardinal. He looked at me with an expression almost like Waldo Bailey’s and practically said, ‘Hello. Come on in.’ “

In his September 3, 1958 “Our Berkshires” column, Borland became the first to advocate for the purchase of the Ashley House from then-owner Edward Brewer. Borland wrote:

“Mrs. Brewer died three years ago. Mr. Brewer is now 80 years old–he looks a spry 65, by the way–and he would like to see the old house in safe hands, properly protected for the future. For a nominal sum he would turn it over to an authorized group, preferably a state agency, complete with its furnishings, glass, pottery and other collectibles.

“The house stands on a seven-acre plot within a stone’s throw of Bartholomew’s Cobble, already a public reservation. As a private museum of regional history it attracts a constant flow of visitors. . . .and visitors must make appointments with Mr. Brewer. He is a generous host and a knowing guide, but he is not there all day or every day. After all, it is his home, not a public place.

“It should be made a public reservation, a monument to the history of western New England. The modern wing, which supplements the original house admirably, would make ideal quarters for the warden of a combined Ashley House-Bartholomew’s Cobble reservation. The house itself should be a museum. It stands on a part of the original Ashley grant, which included the Cobble.

“If I read the Ashley will correctly, most of present Ashley Falls village and its nearby area were owned by Col. Ashley at the time of his death, for he bequeathed some 3,000 acres. He was a prosperous man, a distinguished man, a leader in every sense and a maker of history. His house should become a public monument, not only to Col. John Ashley but to those who came after him and to the history of our hopes and our dreams and our highest purposes. . . .”

Though Borland was proposing the Trustees acquire the house, a group of local volunteers known as “Colonel Ashley House, Inc.,” perhaps inspired by Borland’s article, purchased the property in 1960 and opened it as a museum.

In September of 1961 Waldo Bailey published his paper-bound book Birds of Bartholomew’s Cobble, a companion to a field guide on the ecology and history of the Cobble that he had written in 1948. On April 6, 1963, Bailey suffered a fatal heart attack in a field in Schaghticoke, NY. He was 77 and died as he had lived his entire life–in nature, hunting arrowheads on the land that he loved. On May 22, 1965, Bailey’s Cobble Warden’s Cabin was opened as a museum in his honor, featuring a small sampling of his arrowhead, butterfly, insect, bird and bird nests, and photography collections. In 1995 the new, much larger, visitor center on Weatogue Road opened to the public. The center features a wrap-around deck and public restrooms, is handicapped accessible, and boasts an impressive collection of bird and animal displays, as well as several beautiful Rex Brasher bird prints. The center also has a fantastic library of vintage and classic nature books, including many Hal Borland titles. The Cobble no longer has a full-time Warden, but a Trustees agent is at the center on Saturdays and Sundays from May through September. The Bailey Museum closed to the public in 2001 due to safety concerns and the cabin’s remote location. Bailey’s artifacts were relocated to the new Visitor Center and the Trustees Western Massachusetts office in Stockbridge.

In the spring of 1970 the Trustees announced their intention to “preserve and protect the Cobble’s existing values and to add new and exciting features which will immeasurably enhance the property’s appeal as a scientific, scenic and educational area, we enlarge the present Reservation and add to it a new dimension–the oldest house in Berkshire County, constructed in 1735 by Colonel John Ashley, which overlooks the Cobble.” To this end, the “Bartholomew’s Cobble-Colonel John Ashley House Campaign” was launched on May 17, 1970 at a meeting of campaign members, held at the house. The Ashley House would serve as a museum as well as living quarters for the Cobble Warden, and could be “purchased for the amount of its mortgage, some $20,000.” The Trustees set a fundraising goal of $167,500 for the acquisition of the house and additional properties, including “Ashley Field,” a pasture adjacent to the Ashley House that one walks across to reach the Visitor Center. Berkshire Eagle columnist and long-time Cobble advocate Morgan G. Bulkeley was appointed campaign Chairman, and Hal Borland was named a Co-Chairman for the committee’s Connecticut chapter. The Beinecke Foundation offered to match the first $25,000 raised, followed soon after by a $5,000 gift from The Berkshire Eagle and $6,800 in private donations. By the end of 1970 the campaign had raised $62,000. The Trustees acquired the Ashley House from Colonel Ashley House, Inc. in 1972. On February 10, 1975, the property was added to The National Register of Historic Places.

Hal Borland continued to devote “Our Berkshires” columns to Bailey and the Cobble throughout the 1960s and 70s. His recurring “River Report” monitored progress made in cleaning the Housatonic River, which had been severely polluted by centuries of sewage disposal, chemical waste from paper mills in Pittsfield, Housatonic, Lenox and Lee, and PCB contamination from Bailey’s former employer, General Electric. Hal Borland passed away from emphysema on February 22, 1978. Borland was honored in a trail bearing his name by the Friends of Bartholomew’s Cobble and the Colonel John Ashley House at their Bartholomew’s Cobble Field Day on June 23, 1979. The location of the Borland Trail was specifically chosen for the significance it holds for Borland and the Cobble. In their June 1979 newsletter announcing the Field Day, the Friends wrote:

“In the afternoon, Morgan Bulkeley, Chairman of the Local Committee for Bartholomew’s Cobble, and Mrs. Hal Borland will dedicate the Borland Trail linking the Cobble with the Colonel John Ashley House. Preservation of the Ashley House and its reunion with the Cobble was Hal Borland’s dream, a goal successfully realized with the purchase of 35 acre Ashley Field two years ago.”

The entrance to the Borland trail lies directly across Weatogue Road from the entrance to the Cobble Visitor Center. As you walk the trail through Ashley Field–still farmed for hay today–you have a clear view before you of the lower Berkshires, just as Hal Borland and Waldo Bailey surely did on their visits in the 1950s and early 1960s. Borland wrote of his friendship with Bailey in his article “Rock Garden in a Cow Pasture,” published in the May 1975 issue of Audubon magazine:

“If I were empowered to create a wild garden to suit my whims, I think I would call into being just such a place as Bartholomew’s Cobble. You probably don’t know Bartholomew’s Cobble, which is an old cow pasture with two rugged knolls of marble, situated in the southwest corner of Massachusetts. . . .

“When I said my wild garden would be like the Cobble, I meant the original reservation that was established in 1946. . .it is the original Bartholomew’s Cobble that impressed me nearly twenty-five years ago, when we first came to northwest Connecticut, and it still does.

“S. Waldo Bailey, warden-naturalist in charge of the Cobble from the time it was established till his sudden death in 1963, catalogued 740 species of plants in the original area. Besides the ferns, he listed 493 species of wildflowers, 95 trees, shrubs and vines, 61 mushrooms, 30 lichens, and nine mosses. There probably are a number of species still to be identified, especially among the mushrooms, and the grasses have yet to be catalogued.

“Waldo Bailey practically was the Cobble when I first knew it. We had moved to the far northwest corner of Connecticut, and a neighboring farmer had mentioned ‘the Cobble.’ I asked what it was, and he said they used to picnic there when he was a boy, an old cow pasture that now was a nature reservation. So we drove up there, only a few miles, walked in, and were soon confronted by a big ruddy man in a gray fedora and a gray business suit complete with white shirt and tie. That was Waldo Bailey. When he saw that we knew a chickadee from a starling he gave us the run of the place, asking only that we be careful of the ferns. It was a dry year and the ferns had suffered.

“We became good friends. He was a Massachusetts farm-boy who became a cost accountant and worked for General Electric until the Great Depression. Then, he once told me, he was glad to get out of an office. He took a job with the U.S. Forest Service and felt free again. He left the forestry job to go to the Cobble when it was established as a reservation, and it always seemed to me that he was a part of the place–firm, stubborn as its native limestone, warmed with birdsong, and softened in unexpected places with wildflowers. Birds were his first love, and he had listed 235 species at the Cobble.

“He was a self-taught naturalist with interests that ranged from prehistory and geology to weather and photography, as well as birds and botany. He had a keen eye for Indian arrowheads, could walk across a newly plowed field and pick them up like pebbles. He and a fellow arrowhead collector were walking across a field not far from the Cobble in 1963 when Waldo Bailey died of a heart attack, simply dropped dead. . . .

“Waldo Bailey’s belief, and in a sense the philosophy behind Bartholomew’s Cobble, was put into words one afternoon when I sat with him on the porch of the warden’s cabin, since enlarged and made into a compact little nature museum and library in his honor. We were discussing the change in weather, year to year, and how plants respond. ‘It’s surprising,’ he said, ‘how most plants will live out a bad season and come back. They just pull back into themselves and wait, which isn’t a bad idea. Ferns have been doing that a long time, a good many million years.’ He stared away for a moment, then said, ‘We can learn a lot from places like this. Nature manages things pretty well, manages her own balances. Man upsets the balance time after time, but nature always tries to restore it.’ “

After Bailey’s death in April of 1963, his journals and substantial collections of books, butterflies and insects, arrowheads, artifacts and photographs were inherited by his daughter Priscilla. Priscilla lived her entire life in the Pittsfield home where she was born. Like her father, Priscilla was a great lover of nature and birds, and a long-time member of the Hoffmann Bird Club. Though family members expressed indifference to the journals, Priscilla kept the entire collection intact until she passed away in 2015 at the age of 95. In the last years of her life Priscilla had been friends with Hoffmann Bird Club member Matt Kelly. Kelly was helping Priscilla organize the collection, and had been asked to edit the journals into a much shorter book form, although he had not seen the journals until after Priscilla died. After Priscilla’s passing, ownership transferred to relatives who did not have the means or interest in preserving the collection. They kept and gave away some items, and the rest–including the seventeen binders containing the journals–were thrown into a dumpster.

Kelly was notified by a mutual friend named Sue Cook that the journals were being discarded. Kelly immediately contacted the family, and, through a series of negotiations, saved the journals with the agreement that the Hoffmann Bird Club would assume ownership and their use was strictly on a non-profit basis. Kelly showed the journals to other bird club members including Rene Wendell, and it was decided that the collection should be accessible for public use. Kelly contacted Professor Thomas Tyning at Berkshire Community College for help in making the journals available on the internet, and gave the seventeen binders to Tyning in 2018. Alex Olney, a student at the college on a work-study grant, spent four months scanning and rescanning and creating a search option for the more than four-thousand pages of Bailey’s lifetime devotion to the natural world. The binders containing Bailey’s journals are currently in the collection of the Chapin Library at Williams College in Williamstown, Massachusetts. To view the journals online, visit hoffmannbirdclub.org.

For more on Bartholomew’s Cobble and the Colonel Ashley House, or to plan your visit, go to thetrustees.org.

Copyright 2023 Kevin Godburn All Rights Reserved

. . . . Anatomy of an Award . . . .

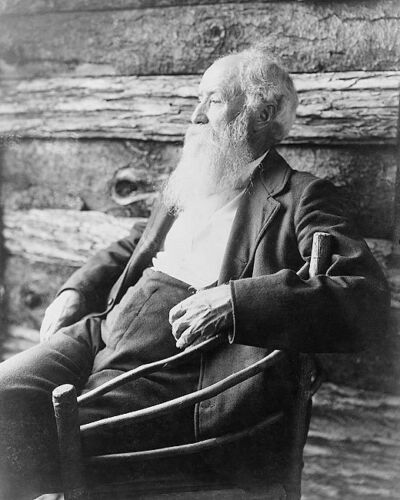

On the first Monday of every April, the John Burroughs Association gathers in New York City and presents their Burroughs Medal to the author of “a distinguished book of nature writing that combines scientific accuracy, firsthand fieldwork, and excellent natural history writing.” Other than perhaps a Pulitzer, no honor is more revered by the nature writer. Since the award’s inception in 1926, Rachel Carson, Edwin Way Teale, John Kieran, Loren Eiseley, and Barry Lopez, among many others, all carried home the Burroughs Medallion.

By the early 1960’s, Hal Borland had established himself as a preeminent voice in the natural sciences. With three undisputed nature classics already to his credit (An American Year, 1946; This Hill, This Valley, 1957; and Beyond Your Doorstep, 1962), Borland had long ago earned the respect and admiration of peers and fans, and had amassed a shelf-full of awards for his efforts. But the Burroughs Medal had thus far eluded him.

Borland’s journey to the Burroughs Medal would be a long one, the culmination of a campaign that began rather innocently in a letter to George Stevens, Borland’s editor and good friend at JB Lippincott Co. On April 3, 1962, Borland wrote Stevens:

“I’ve never gone in for honors, as such, but there are a couple coming up that would interest me. One is the John Burroughs Medal, and the other is one of the Columbia School of Journalism’s Alumni Awards, given annually. I don’t know what one does about such things, or whether you just sit and work and wait to be tapped. But I doubt that it’s quite proper to call. . . whoever is in charge of the Burroughs group, Richard Pough I think, and say, ‘It’s Borland’s turn.’ Anyway, maybe it ain’t Borland’s turn. Do you know about such things? Do any of your colleagues? I feel quite brash even mentioning this to you, but I would be proud of a feather for my cap, and it wouldn’t hurt the books, would it?”

And so began a six-year skirmish that would cast Borland and two of his most ardent supporters against the Burroughs Association’s indomitable Secretary-Treasurer, Miss Farida A. Wiley.

Farida Anna Wiley was born in Sidney, Ohio in 1887, the daughter of ranchers who raised percheron stallions and devoted free time to planting trees. At an early age, Farida (pronounced Fareeda) developed a keen interest in birds and nature. By age eleven she was sending reports on bird sightings and migrations to the U.S. Biological Survey in Washington. She immersed herself in the study of the natural world, a lifelong passion that would make her a self-taught authority on plants and trees, insects and ornithology.

In 1919 Farida moved to New York City to live with her older sister Bessie and brother-in-law Clyde Fisher. George Clyde Fisher was born in Sidney on May 22, 1878. Like Farida, Clyde developed an early fascination with nature, and astronomy in particular. He received his A.B. degree from Miami University in 1905, and he and Bessie were married that same year. After Fisher earned his Ph.D. in botany from Johns Hopkins University in 1913, he and Bessie relocated to New York where Clyde took a position as Associate Curator for the Department of Public Education at the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH). When Farida arrived in 1919, Fisher helped her land a part-time job teaching nature studies to blind students at AMNH, the beginning of her association with the Museum that would last until 1981.

When he was a youngster in Ohio, Clyde began a correspondence with John Burroughs, and over the years the two developed a close friendship. On November 6, 1915, Clyde and Bessie made their first visit to Burroughs Riverby home on the Hudson River in West Park, NY. Clyde, an accomplished photographer, later recalled; “Knowing that Mr. Burroughs did his writing in the forenoons, we proposed not to disturb him until lunch time. . . .I had brought my camera, hoping to get one picture of the great poet-naturalist. Before noon I started out to secure a few photographs about his home. . . .While focusing my camera on the Summer House, I was discovered by Mr. Burroughs, who appeared at the door of his Study, and after cordially greeting me, said, ‘I thought you might like to have me in the picture.’ ” Clyde took three photographs of Burroughs that day: “So my wish was more than fulfilled on that first visit.” After lunch, Burroughs led his guests on a walk to his cabin retreat, Slabsides, discussing native plant and animal life along the way and recalling past visitors. As they said goodbye at the railroad station in West Park that evening, Burroughs told Clyde, “Whenever you want to come to Slabsides, the key is yours.”

Clyde and Bessie visited Burroughs and “camped in this mountain cabin, for two or three days at a time, about twice a year since that first visit.” Burroughs would typically receive guests at Slabsides in the spring and fall, but preferred to spend summers at Woodchuck Lodge, at his birthplace in Roxbury, New York in the Catskill Mountains. During a visit to Woodchuck Lodge, Clyde and Burroughs lounged in the hay barn discussing the work of Thoreau. While Burroughs spoke highly of Thoreau, he also “referred to certain peculiarities and to a number of surprising inaccuracies” in Thoreau’s writing. But Burroughs concluded, “I would rather be the author of Thoreau’s Walden than of all the books I have ever written.”

Clyde and Bessie visited Burroughs and camped at Slabsides over the weekend of November 6-8, 1920, the fifth-year anniversary of their first visit to Riverby. Also in attendance were a small group of Burroughs’ close friends, and Bessie’s sister, Farida Wiley. On Sunday the seventh, Burroughs cooked his “favorite brigand steaks” for lunch and spent the afternoon with the group, discussing his latest book, Accepting the Universe, and examining the surrounding plant life. Clyde “made what proved to be the last photographs of him at Slabsides,” and the last of the nearly two hundred photos that Fisher had taken of Burroughs since November of 1915. (Several of Clyde’s photos were published in The Life and Letters of John Burroughs, Houghton Mifflin Company, 1925). John Burroughs passed away the following spring, on March 29, 1921. Several months after his death, Farida Wiley was among the small group of friends who founded the John Burroughs Memorial Association to honor and preserve the legacy of the beloved naturalist.

Wiley became a full-time member of the AMNH educational staff in 1923, and was named Director of Field Courses in Natural History and Honorary Associate in Natural Science Education several years later. As part of her “Natural Science for the Layman” course, Wiley conducted weekend field trips to sites in Staten Island, Westchester, Long Island, New Jersey, and National Audubon Society reserves in Connecticut. For many years Wiley also taught nature and ornithology courses at Pennsylvania State College and New York University, and from 1947 to 1967 led a summer program at the Hog Island Audubon Camp in Maine. By the early 1950’s, Wiley had been named Assistant Chairman of the AMNH Department of Public Instruction, and was an associate in the Museum’s Conservation and Ecology departments. Wiley’s first book, Ferns of Northeastern United States (1936), was for many years the definitive field guide on the subject. In the 1950’s and early 60’s, Wiley edited the Museum’s “American Naturalists” book series, collections of excerpts from naturalists including John Burroughs, Ernest Thompson Seton and Theodore Roosevelt. Farida never married–she was forever “Miss Wiley.”

In the mid 1930’s Farida began leading spring and fall migration bird walks in Central Park. Walks were held Tuesday and Thursday mornings, with two walks each day, departing at 7:00 and 9:30am. Walks were held rain or shine, and proved an immediate success. The walks often attracted seventy or more birders, many of whom were regulars who attended multiple walks each year. Farida kept a mailing list of all her birders, including descriptions of each to help remember their names. On days when birds were few, Farida simply instructed the group on the Park’s tree, plant and insect life instead. “She’s a walking encyclopedia,” said one devotee. The press took notice of Miss Wiley; Sports Illustrated and The New York Herald Tribune ran features. The New York Times described her as “bluff, wiry, freckled and partial to tweed suits.” The Washington Post wrote, “She was fond of rust-colored tweeds, sensible shoes and long-billed caps and tam-o’-shanters. She walked at a gallop, binoculars in hand. . . .She wore a pince-nez on her nose. . .her eyes were clear, fierce and alert, crackling with the spirit of scrutiny.” Farida frowned upon disturbing or removing anything from the Park: “We gather nothing in a sanctuary. We do not smoke in a sanctuary.” When asked about the seedy characters they encountered in the early morning park, Wiley replied, “We just step right over them.”